Toll Free Helpline Number

18002101616

Book on Whatsapp

9892101616

The Carotid Conundrum: Unraveling Splaying- A Comprehensive Guide To Carotid Space Lesions

Case Study

Thu Jan 02 2025

CLINICAL DETAILS

A 44-year-old female presents with a history of multiple episodes of giddiness. The patient reports noticing swelling within her oral cavity, specifically in the area posterior to the right tonsillar pillar for 6 months. On clinical examination, there is no palpable swelling in the neck. However, a significant parapharyngeal swelling, approximately 4x4 cm in size, is observed in the oral cavity posterior to the right tonsillar pillar. This swelling is associated with a deviation of the uvula to the left. The clinical findings suggest a possible mass or lesion in the parapharyngeal space, warranting further investigation to determine the underlying aetiology.

IMAGING FINDINGS:

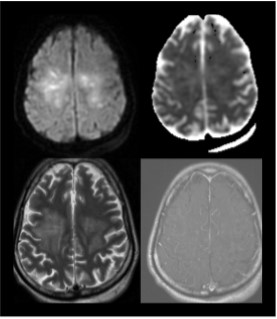

MRI reveals a well-defined, oval-shaped lesion in the right carotid space, measuring 3x4x5 cm. The lesion causes splaying of the internal and external carotid arteries and extends medially into the right parapharyngeal space. The lesion is iso to hyperintense on T1/T2WI and shows homogeneous postcontrast enhancement.

CT angiography of neck and brain showed the above-mentioned lesion to be hypoenhancing in the arterial phase.

The differential diagnoses considered were carotid body tumour, cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma and vagal schwannoma. Vagal schschwannomas displace the carotid arteries anteriorly rather than splaying them. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannomas displace the carotid arteries anteriorly but occasionally splay the internal and external carotid arteries without encasement. Carotid body tumours are usually pulsatile in nature, show multiple internal flow voids, splay and encase the carotid arteries, and show intense early enhancement followed by rapid washout. However, in our case, the mass showed progressive enhancement. Hence, in the given clinical setting and after reviewing the radiological features, a probable diagnosis of schwannoma was made.

FOLLOW-UP

Patient underwent surgery and it was found to be arising from the hypoglossal nerve and the biopsy revealed schwannoma.

DISCUSSION

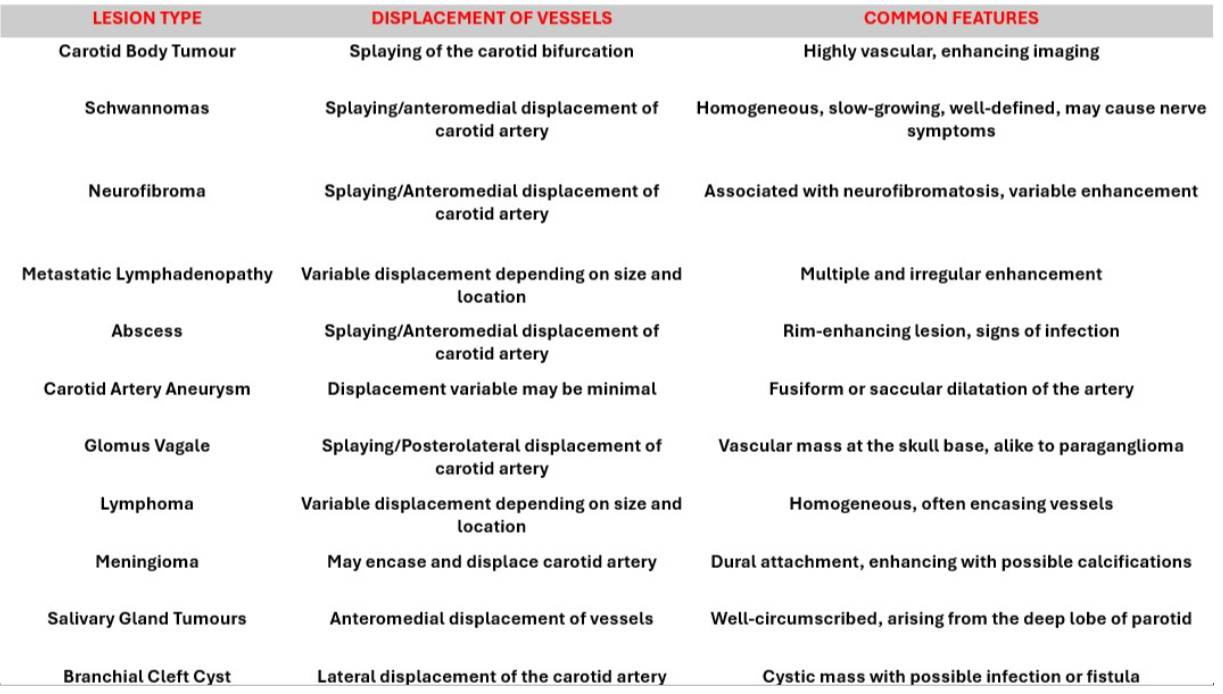

Here are the possible causes of Lyre sign and the imaging features:

CONCLUSION

The ‘Lyre’ sign describes the characteristic splaying of the carotid artery bifurcation due to a carotid body tumour on conventional carotid angiography. This sign, however, is not diagnostic of carotid body tumours. An accurate diagnosis is, therefore, essential before embarking on invasive procedures such as biopsy or aspiration to prevent potential catastrophe.

As this case exemplifies, the road to a definitive diagnosis demands a synthesis of clinical acumen, imaging finesse, and sometimes, surgical intervention.

Bottomline: “Not all that splays is carotid body tumor”!!

Dr Adarsh Ishwar Hegde

KH site, Manipal

Related Blogs

Case Study

A Rare Case of 45,X/46,X,i(X)(q10) Mosaicism : Variant Turner Syndrome

Introduction:

When one of the two X chromosome is missing partially or totally(45,XO) , it causes Turner syndrome(TS), a disorder that impacts only females affecting 1 in 2000 to 1 in 2500 live births. Short height, webbed neck, lymphedema, low-set ears, wide-set nipples, heart malformations, skeletal and kidney abnormalities and gonadal dysgenesis are a variety of medical and developmental issues that can result from TS.

Care report:

We reported a case of 28-year old female patient evaluated for infertility, the patient’s menstrual history indicated with the last menstrual period recorded on 13/01/2025. The patient underwent multiple fertility evaluations, including transvaginal sonography, which suggested premature ovarian failure. Incomplete information of hormonal analysis of the patient was given which showed normal range of Thyroid stimulating hormone(TSH) 2.87mIU/L & Prolactin(PRL) 7.17ng/mL and HBA1c test of 5.0% which is considered as normal.

Karyotyping of the patient revealed an uncommon form of TS, isochromosome mosaic karyotype 45,X/46,X,i(X) (q10), which

accounts for 8-9% of TS cases in women, worldwide. Due to the unusual features, each case should be thoroughly examined to

identify any potential issues.

CYTOGENETIC ANALYSIS:

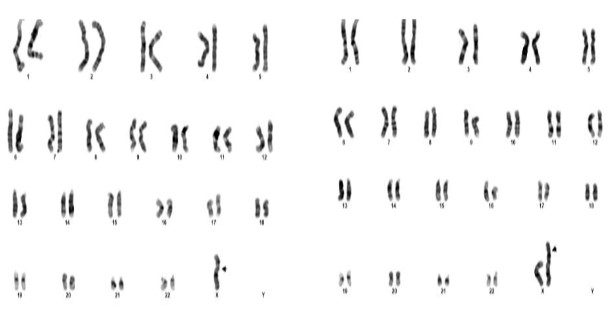

Provisional diagnosis showed a rare mosaic 45,X/46,X,i(X)(q10) karyotype identified with GTG-banding

Figure 1: Karyotype of 45,X/46,X,i(X),(q10)

The cytogenetic analysis of the patient revealed two cell lines 45(X); 46(X), i(X), (q10,q10) indicates mosaicism for Turner syndrome. The 45,X represents a cell line with monosomy of X chromosome characteristic of Turner syndrome found in 38 cells. The cell line 46, X ,i(x),(q10,q10) showing one normal X chromosome and an isochromosme for the long arm of another X chromosome, found in 12 cells. This condition is referred to as isochromosome mosaicism of Turner syndrome.

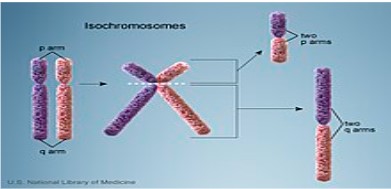

This condition is caused by a structural abnormality of the X chromosome, specifically an isochromosome, where the long

arms of the X chromosome are duplicated while the short arms are missing. This typically results from a failure in proper chromosome separation during cell division, leading to mosaicism.

Figure 2: Isochromosome formation

Individuals with mosaic Turner syndrome exhibits a wide range of symptoms including short stature, primary ovarian insufficiency or premature ovarian failure, infertility, webbed neck and broad chest, lymphedema, hearing loss, cardiovascular anomalies, skeletal abnormalities and lack of pubertal development. Therefore, regular follow-ups and multi-disciplinary approach are essential for optimal management of the condition.

CONCLUSION:

In this case study, the presence of 45,X/46,X,i(X)(q10) has confirmed the diagnosis of an isochromosome mosaic Turner syndrome thus facilitating prompt management. It highlights that Turner syndrome exhibits significant phenotype heterogeneity, with clinical symptoms varying according to the particular karyotype. The wide range of TS variations is demonstrated by the fact that patients with isochromosome X mosaicism have milder symptoms and fewer complications than those with the 45,X karyotype. The results of the patient highlights the value of treating TS with a comprehensive approach.

Genetic counseling: Genetic counseling is recommended to help patient understand her condition, manage health risks and explore fertility options.

Case Study

Decoding the Masquerader: A multi-organ tour of Melioidosis from radiology to reality!

Decoding the Masquerader: A multi-organ tour of Melioidosis from radiology to reality!

This case series has been contributed by Dr Sharadhini Karanth – from KH Manipal.

{This was selected as an educational exhibit at the European Congress of radiology and received widespread appreciation}.

CLINICAL CONTEXT

Melioidosis is an infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. This environmental saprophyte is commonly found in soil and stagnant water in tropical and subtropical regions. The organism can enter the human body through skin abrasions or wounds, inhalation of contaminated dust, or ingestion of contaminated water [1]. Individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those with diabetes, chronic alcoholism, renal or liver failure, or malignancies, are at significantly higher risk of infection.

The disease is geographically expanding, with cases reported in new endemic regions, highlighting the growing global health concern. The signs and symptoms are non-specific and overlap with several diseases, including tuberculosis. Thus melioidosis, ‘the great mimicker’ of many diseases, is grossly underdiagnosed and underreported across the tropics, including India[2]. Melioidosis presents with a wide spectrum of radiological manifestations, ranging from localized abscesses to systemic involvement of multiple organs, including the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, and central nervous system. The variability in presentation underscores the critical

importance of correlating imaging findings with clinical history and laboratory results to achieve accurate diagnosis and effective disease management.

Results or Findings

The most common site for melioidosis infection is the lung, followed by the spleen and liver. Other organs such as kidney, prostate, brain and musculoskeleton can also be involved. [1]

PULMONARY MELIOIDOSIS

Chest radiography is useful for diagnosis [2]. However CT scans of the chest can give more detailed information.

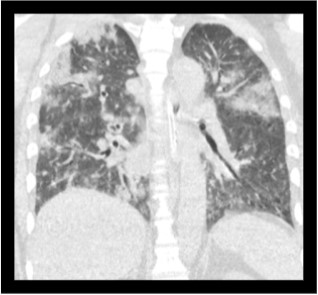

Pulmonary melioidosis predominantly presents as pneumonia, accounting for nearly half of reported cases [3]. Radiologically, it often manifests as upper lobe infiltrates with or without cavitation. Acute forms may show diffuse nodular infiltrates or discrete lobar consolidations, with septicemic cases favoring upper lobes and non-septicemic cases affecting lower lobes.3. Subacute and chronic forms progress slower, with mixed nodules, patchy opacities, and minimal fibrosis. Differentiation from tuberculosis can be challenging.

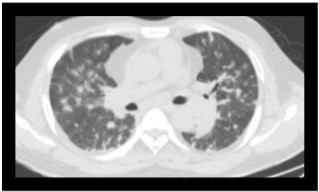

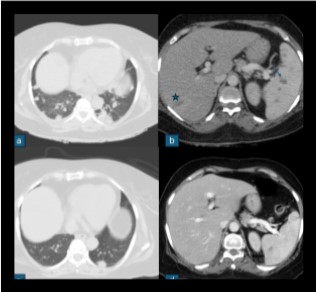

Fig 1: In a culture proven case of melioidosis, an axial section of CT in a lung window shows multiple scattered nodules.

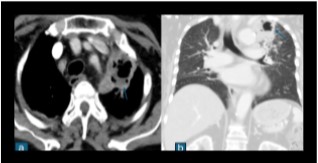

Fig 2: Contrast enhanced CT scan of a proven case of melioidosis showing a cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the apico-posterior segment of the left upper lobe s/o lung abscess.

Fig 3: Coronal sections of the CT thorax show multiple patchy areas of consolidations.

Though melioidosis spares the lung apex, less fibrosis, absence of pleural effusion with no mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and presence of confluent consolidation go more in favor of melioidosis1. Pleural effusions, empyema, pneumothorax, and hydropneumothorax are rare but possible complications, often linked to cavity rupture5.

VISCERAL MELIOIDOSIS

Spleen

The spleen is the most commonly affected extrapulmonary visceral organ in melioidosis. Splenic lesions are typically multiple, small, and discrete, ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 cm. Larger multiloculated lesions, subcapsular collections, and perisplenic extensions may also occur [4]. Splenic abscesses, more frequent in melioidosis than other infections, can present as microabscesses or large multiseptate lesions. Imaging findings include hypoechoic lesions on ultrasound and hypodense lesions on CT scans. A characteristic “target sign” or “bull’s eye” lesion may be seen, and larger abscesses may demonstrate a honeycomb or necklace sign 6. Splenic vein thrombosis

and infarcts are additional complications in systemic melioidosis.

Liver

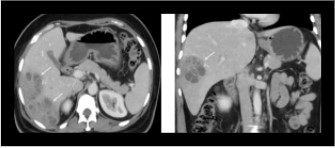

Hepatic melioidosis shares similar radiological characteristics with splenic involvement, often presenting as single or multiple abscesses. These lesions range from small hypoechoic microabscesses to large multiloculated and multiseptate abscesses 1. Larger abscesses, exceeding 2 cm, may display a honeycomb or necklace sign

Fig 4: Axial and coronal sections of contrast enhanced CT showing a multiloculated abscess in the right lobe of the liver.

on imaging, particularly on ultrasound and CT scans. The simultaneous presence of hepatic and splenic abscesses is highly suggestive of melioidosis, especially in patients with comorbidities or a history of travel to endemic regions. Differentiation from other infections, such as tuberculosis or fungal abscesses, is often required due to overlapping imaging features 1.

Fig 5: In a known case of metastatic Ca breast, on chemotherapy presented with fever. Fig a shows variable sized lung nodules, Fig b shows ill defined hypodense lesion in segment VII of liver (marked with star) and multiple hypodense lesions in spleen (marked with arrow). Blood culture isolated B. pseudomallei and treated with intravenous meropenem. Follow up scan Fig c, d shows significant decrease in the lung nodules, resolution of liver lesion and significant decrease in the splenic lesion.

Pancreas

Pancreatic melioidosis is less common and usually occurs as part of multiorgan involvement. CT imaging reveals multifocal microabscesses or focal large abscesses, predominantly in the pancreatic body. Associated findings may include surrounding inflammation, splenic vein thrombosis, and peripancreatic fat stranding. 3

Kidneys

Varies from multiple ill-defined or well defined hypodensities, rim enhancing fluid collections, abscesses, and pyelonephritis. Involvement is more often bilateral and multiple rather than a localized or unilateral disease.5

Prostate

Manifests as abscesses, predominantly in the peripheral zone, detectable via CT or ultrasound imaging.

MUSCULOSKELETAL MELIOIDOSIS

Involvement is seen in 5–48% of cases [5] , manifests as osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, synovitis, or soft tissue abscesses

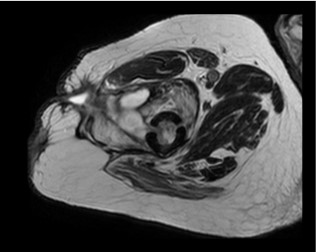

Fig 6: Intramedullary altered signal intensity of the femur with cortical breachforming irregular abscess collection within the vastus lateralis and intermedius muscle extending to subcutaneous plane, from which a sinus tract extend and reach to the skin surface.

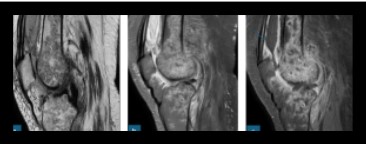

Fig 7: Case of septic arthritis, culture proven Melioidosis. Fig a, b, c sagittal sections of T2 , PDFS and post contrast sequences shows multiple irregular peripherally enhancing intercommunicating hyperintense on T2WI collections in visualised portion of shaft of femur and proximal tibia. Knee joint effusion noted extending into supra patellar bursa showing peripheral post contrast enhancement (marked with arrow).

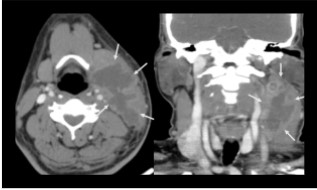

Fig 8: Axial and coronal sections of contrast enhanced CT scan of the neck shows multilobulated predominantly hypoattenuating mass showing peripheral contrast enhancement, extending under the left sternocleidomastoid muscle, from the posterior cervical space to the submandibular space anteriorly, involving the regions of the II and III lymph nodes levels, displacing the structures of the carotid and pharyngeal spaces medially and the left submandibular salivary gland anteriorly. Incision and drainage was done. Culture sensitivity showed Burkholderia cepaciae and treated with inj Meropenem 1g for 10 days.

It often affects weight-bearing joints (knee, hip, ankle) and bones via hematogenous spread or adjacent infection. Imaging reveals joint effusion, bone erosion, and abscesses, with MRI being the most sensitive modality for diagnosis. 3

NEUROLOGICAL MELIOIDOSIS

Affecting only 4% of cases3, presents significant challenges due to its high mortality rate and severe morbidity among survivors. The radiological manifestations of neurological melioidosis encompass diverse findings, with rim-enhancing lesions and leptomeningeal enhancement being most characteristic. While imaging may be normal or show non-specific changes, key features include abscess formation, meningoencephalitis, brainstem encephalitis, transverse myelitis, paraspinal collections, and sinonasal involvement. Brain parenchymal disease can manifest as both micro and macro-abscesses with encephalitic features.

Fig 9: Intra-axial T2/ FLAIR hyperintensities noted along bilateral corticospinal tracts involving subcortical and deep white matter of bilateral frontal (right> left), left parietal lobes showing patchy areas of diffusion restriction, patchy areas of pseudonormalization on ADC and post contrast enhancement, s/o encephalitis/cerebritis.

CONCLUSION

Melioidosis is a significant public health concern due to its increasing endemicity and ability to mimic other infections and involve multiple organs. Awareness of these radiological patterns, coupled with clinical history such as septicemia or travel to endemic regions, is crucial for early diagnosis. Recognizing these features allows for timely and appropriate management, preventing complications of this versatile and potentially fatal infection.

References

- Amin, Dhanush, Sridevi Chinta, Anu Kapoor, M. V. S. Subbalaxmi, D. Amulya Reddy, A. Neelima, and Jyotsna Yarlagadda. “Imaging Case Series of Melioidosis: The Great Masquerader.” Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 54, no. 1 (February 27, 2023): 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-023-00994-2.

- Mohapatra, Prasanta R., and Baijayantimala Mishra. “Burden of Melioidosis in India and South Asia: Challenges and Ways Forward.” The Lancet Regional Health - Southeast Asia 2 (July 1, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.03.004.

- Wanaporn Burivong, Sunsiree Soodchuen, Panitpong Maroongroge, Prasit Upapan, and Vichit Leelasithorn. “Radiographic Manifestations of Melioidosis: A Multi-Organ Review.” Medical Research Archives, Radiographic Manifestations of Melioidosis: A Multi-organ Review, 5, no. 3 (March 2017).

- Dhiensiri, T., S. Puapairoj, and W. Susaengrat. “Pulmonary Melioidosis: Clinical-Radiologic Correlation in 183 Cases in Northeastern Thailand.” Radiology 166, no. 3 (March 1988):711–15. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.166.3.3340766.

- Alsaif, Hind S., and Sudhakar K. Venkatesh. “Melioidosis: Spectrum of Radiological Manifestations.” Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences 4, no. 2 (2016): 74–78. https://doi.org/10.4103/1658-631X.178286.

- Currie, B. J., D. A. Fisher, D. M. Howard, J. N. Burrow, D. Lo, S. Selva-Nayagam, N. M. Anstey, et al. “Endemic Melioidosis in Tropical Northern Australia: A 10-Year Prospective Study and Review of the Literature.” Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 31, no. 4 (October 2000): 981–86. https://doi.org/10.1086/318116.

- Ong, Sidney Ching Liang, Mina Mustafa Mahmood Alemam, Nor Aniza Zakaria, and Nur Azidawati Abdul Halim. “Honeycomb and Necklace Signs in Liver Abscesses Secondary to Melioidosis.” BMJ Case Reports 2017 (October 19, 2017): bcr2017222342, bcr-2017–222342. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-222342.

Case Study

An Indian Spring - Unrest in the Chest

A 57 year old lady presented with a left chest wall nodule with a 3 week history. There was no other contributory history. This was a referral from an interventional radiologist and a core biopsy was submitted for histopathologic analysis. The radiologist’ impression included a soft tissue tumour and a hemato-lymphoid malignancy. No whole body imaging was available at the time.

The biopsy indicated a high grade, poorly differentiated large cell malignancy (pending immunohistochemical characterisation). Lesional tumor cells were set in a syncytial growth pattern with a streaming pattern seen focally, and found infiltrating between muscle bundles of the chest wall. Significant tumor emperipolesis was recorded.

Basis the morphology, a hemato-lymphoid malignancy was favoured over a soft tissue tumor. We circled back to the radiologist inquiring about the presence of multiple lymph nodes and/or lymph nodal masses or hepatosplenomegaly, if any. Whole body imaging was then ordered and lo and behold there was multiple lymphadenopathy found including, in the mediastinum together with bilateral renal enlargement present.

Stop press: in light of new radiologic findings coming to the fore, and presence of significant tumor emperipolesis as morphologic finding, our thoughts also turned to ‘biphasic squamoid’ papillary renal cell carcinoma (BPRCC) where emperipolesis is now accepted as a constant feature. However, in the present clinical context of chest wall nodule with multiple nodes in mediastinum and bilateral renal involvement, this was mooted as a remote possibility.

Immunostains were ordered for lymphoma work up and tumor cells were found reactive for CD45, CD20, CD30 and negative for T cell marker, CD43 as well as for ALK1. Cut to the chase, we now had a diagnosis favouring CD30 + anaplastic variant of DLBCL rather than a lymphocyte depleted Hodgkin disease which is the closest differential on immunohistology; absent a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and diffuse CD30 reactivity in the given case.

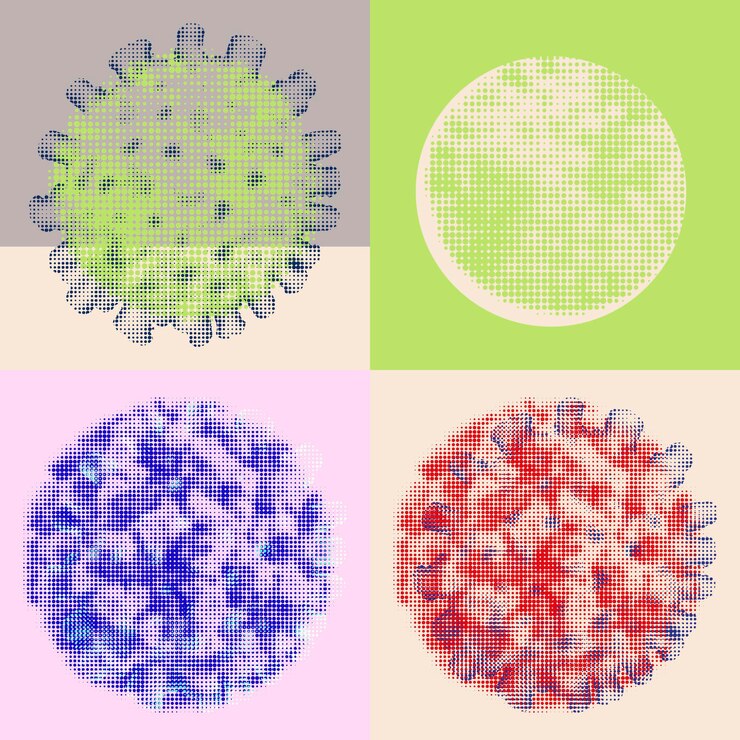

Next, a Hans algorithm was employed using CD10, bcl-6 and MUM1 to broadly stratify the DLBCL into two molecular prognostic groups: Germinal centre B cell (GCB) and activated B cell/ non GCB subtype. Note the GCB subtype has a better prognosis than the non GCB subtype. Our case yielded a CD10 — bcl 6 + and MUM1 + phenotype indicating a non GCB subtype and it follows therefore; a worse prognosis. Further and more, the International Prognostic index (IPI) lends itself handy as a clinical tool for predicting overall and progression free survival in DLBCL- something which is outside the scope of the current discussion.

No conversation on the DLBCL universe is ever complete without a refrain on ‘double hit’ and ‘triple hit status’ of the lymphoma. The double hit and triple hit status of DLBCL implies genetic rearrangement and/ or translocation of c- myc, bcl-2 or bcl-6 resulting in protein overexpression of these proteins (positive cut offs being defined at 70% of cells for c-myc and bcl-6 and 40% for bcl-2). Although protein expression by IHC is not a surrogate for cytogenetic testing, protein overexpression for c- myc, bcl-6 and bcl-2 can reliably indicate likely probability of double hit and triple hit status of lymphoma. Both double hit (DL) and triple hit lymphomas (TL) portend worse prognosis with poor response to chemotherapy and higher recurrence rates. In this instance, probability of a double hit lymphoma was considered less likely as c-myc and bcl2 proteins were not overexpressed in our case.

The final diagnosis offered was CD 30+ anaplastic variant of DLBCL, extranodal.

The received wisdom on testing for DL and TL status is that samples must be subjected for cytogenetic FISH based testing as it is more reliable and specific for these targets, and the same is incorporated into routine clinical practice.

As is wont to happen in non hospital based settings, the patient was referred to a tertiary care referral centre and lost to follow up.

To sum up, here we have an unusual extranodal presentation of a DLBCL (note extranodal DLBCLs are generally confined to gastrointestinal, skin, soft tissue, bone and genitourinary tract) wherein we are able to achieve prognostic stratification into two broad molecular subgroups on a targeted image assisted biopsy, enabling a ‘less is more’ approach to tumor diagnosis and prognosis with minimally invasive techniques of tissue sampling.